An Adoptee’s Experience: Family, Fortitude & Forgiveness

A Story of Searching for Identity and Belonging

This personal essay originally appeared in the Barker Adoption Foundation’s Blog

At 43 years old through an ancestry search I found more than my DNA. I found family and that freedom-type of forgiveness that usually only comes from what feels like an impossible combination of acceptance, release and grace. Just like the scattered pieces of a mosaic, I received broken and incomplete pieces of information throughout my life whenever I asked about my ethnicity and the circumstances of my birth that led to my adoption. I can’t recall a time when I was not searching, longing, for something that was missing. What I was searching for could shift from mundane to large and lofty – it wasn’t always clear. As a young adult, I searched for a good time. As a wife, I searched for passion and security, and as a mom, I wanted stability and support. I couldn’t get settled. I was happy, adjusted, successful personally and professionally, yet I was never satisfied.

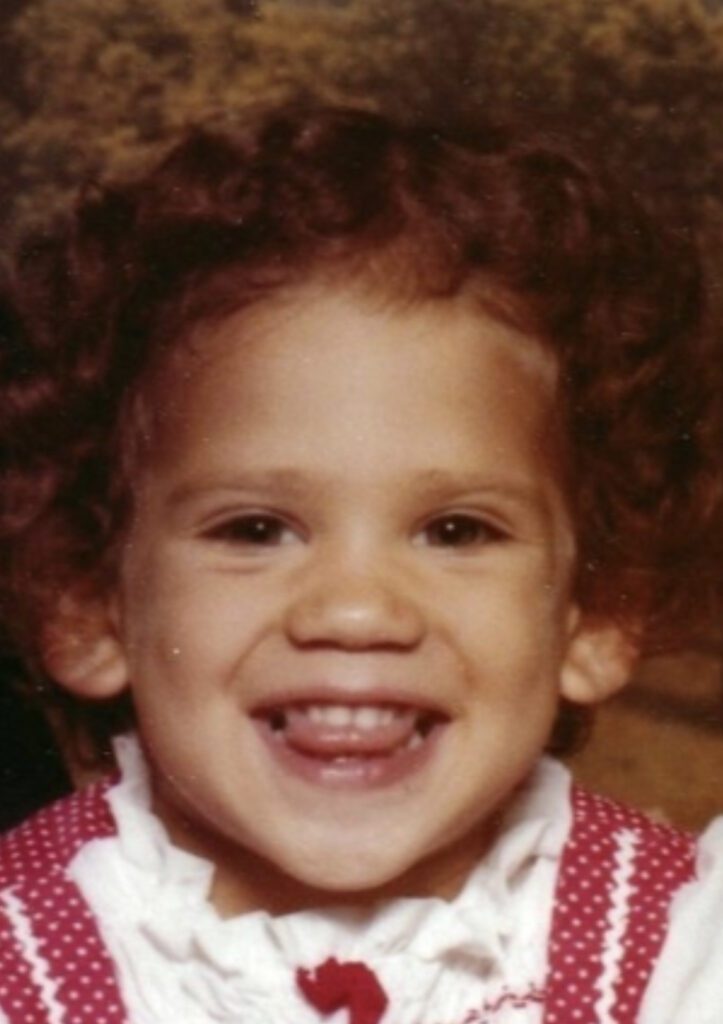

If I go further into the memory vault to a single-digit age when my family lived in the olive-green split-level, I have memories of daydreaming and searching for someone who looked like me. Someone with green eyes and this puffy brown, thick, curly hair and a lean muscular body under a not totally Caucasian cover. I imagined she’d know how to style my hair or have an outie belly button too. Often referred to as exotic, maybe she was from the islands. I often asked my parents (who raised me) about my parents (who made me). What did the adoption agency say when they got me? I knew nothing from the day other than they got a call from someone at the adoption agency and the voice on the line said they had a little girl. My dad said, “we’ll take her” and that was that, like carry-out dining. The answer never changed and new information was never uncovered. Every time it sounded so simple, but to me it felt so complicated. Too many unknowns and too much gaslighting in a ‘pass the peas’ kind of way. Grateful to have been placed in a loving and nurturing forever home, I dared not ask too much out loud, so I definitely kept too much in.

Grateful to have been placed in a loving and nurturing forever home, I dared not ask too much out loud, so I definitely kept too much in.

Bethany Fraser

Occasionally, I stopped interrogating my parents because maybe they really didn’t have any information from those birth records beyond what they told me. “You’re Russian like our friend Sue, honey. They didn’t tell us much anything else.” Some days, I’d believe their version of my truth. But wonder and curiosity always resurfaced. More dead ends. More distractions. Life got busy with school or marriage or kids. Sometimes I was happy enough with the life I was living that I’d forget about searching, and the fog would lift. Yet I’d always land in the same space, down the rabbit hole of searching with all the tools available to me. For decades, this curiosity tug and pull continued. Without knowing, I mastered the tender (and exhaustive) balance of remaining inquisitive, yet sensitive, in my search for confidence and answers. In 2020, at age 43, I did an ancestry search and the beautiful and whole mosaic was revealed.

Over 40 years ago, on a fall October night, a pint-sized young woman started feeling contractions. The youngest sister of three gave birth to a baby girl and named her Angelina Marie. The young mother was barely 19 and white. The father, a few years older, was Black. The girl’s parents, now grandparents, gave their daughter an ultimatum…get rid of Angelina Marie or we’ll get rid of you.

Against the backdrop of racially divided Buffalo, New York, the young, scared, tiny thing of a woman chose her baby and her boyfriend, the baby’s father, and left her family behind. Disowned and afraid, she moved in with her boyfriend, who left school, picked up a variety of jobs, and kicked out his roommates to create a home for his new family. His extended family pitched in with babysitting and support the best way they knew how. The new father thought they should marry; the mother wasn’t so sure. As weeks passed, her family and friends continued to pressure her to give up the baby. Suffering in silence, she caved to the pressure from all directions. She packed up her sparse belongings and left quietly in the cold while her boyfriend, and father of the baby, was at work.

The young father came home after another long day at work to an empty house. No baby, no baby’s mother, no clue. In a frantic search, before cell phones or social media or Amber alerts, the father tracked down the mother and learned Angelina Marie was taken to a neighboring town’s social services office and placed for adoption. The circumstances surrounding Angelina’s birth were captured in paperwork archived in New York, a closed-adoption state at that time. The yellowing paper that held the secrets of my identity would stay sealed as if it was daring me to be bold enough to figure it out on my own. I was the baby described in the paperwork, deemed “special needs’’ because I was biracial, although that piece would remain archived. After a few weeks in foster care, I was placed in a loving Christian, Caucasian, forever home, and never told I was considered “special needs” simply because of my mixed race, only told I was Eastern European, Russian specifically.

It was a chilly December day, shortly after my 30th birthday, and one month before I was getting married and ready to settle into family plans of my own, when my birth mother found me. We had a series of awkward exchanges over email, she too, withholding secrets of her own. She wouldn’t share details of my birth father or details surrounding the circumstances of my birth. She wasn’t ready for me to meet my half-sister. She was “young and couldn’t remember” was the best information I could get. And she promised her mother she wouldn’t tell my half-sister about this until she was 18 years old — which was eight years away still. Later I would come to understand her responses, and her reasoning driving the lack of information. At the moment she was another person to integrate, another piece of the mosaic. Another person who was hiding information from me. I was too close to completing that mosaic, still in the search, and couldn’t quite yet see it as a beautiful design. I let it go for another decade.

Just before the summer solstice in 2020, protesters were flooding the streets and finally standing up for another Black man murdered at the hands of white police. I was enraged. Triggered. My protest followed in the form of a DNA test. It was as if my blood was bubbling and had something to say. I spit in a cup because I wanted to know. Because I wanted my sons to know. Because we deserved to know. Who am I? Even more specifically the question evolved into… am I Black and why is everyone hiding?

One month later, I got my results: 50% Eastern European (Ukranian and Belarusian) on my mother’s side and 32% African and 18% a random European combination on my father’s side. For the next 72 hours, I’d put together my virtual family tree. A few months afterwards, I met my birth father, who filled in the blanks with the broken pieces. I stepped back at last, and before me was a beautiful mosaic.

Technology made possible my search for ancestry and my self-discovery. I found my whole truth, and with it, I found belonging. I found my birth family. Through uncovering my truth, several things happened. Healing. I could really see my brave and beautiful birth mother for her strength and have compassion for what she went through. She also has experienced healing being freed from a secret she was forced to keep about a traumatic decision she was forced to make. Do I carry her anxiety, trauma and fear in my bones these days as my own? My broken and brave biological father was able to begin healing through a reunion with his first-born, who was taken from him in secret, along with his rights, and because of his Blackness. He was left with no baby, no choice, no closure.

My father died last year. The man who nurtured me, protected me, and educated me. Whose toes I’d stand on whenever a Billy Joel song came on. I was in the sparkle in his eye, and my name was etched on his heart, and I drove him mad with my sass. My father was the first man I loved, and from him I learned to love. I was alone with my dad when he died. I wrapped his arms around me and curled up in bed next to him. I snuggled into his chest and wept. I washed his hands and face and repeated messages of my love and gratitude for the life he provided me until the very end of his own. When Dad’s big heart finally stopped and he took his last breath, I was filled with gratitude. I then began the painful process of grieving. Because adoption is layered and nuanced the discovery is too. The next layer is one I didn’t expect.

I arrived at my parent’s best friends around midnight the night my father died. We stayed up late together talking about all the things up to and including the past year. We decided the pandemic probably took a big toll on my father’s health, along with so many years of caring for my mom and her dementia. My aunt and uncle didn’t know about my DNA search, and I pulled up the results in their kitchen. “Honey, we knew,” my Aunt said.

What do you mean you knew? Nobody knew. I just found out, and I’m 45. Certainly, she meant “we knew” as in “we assumed” I was mixed with something like most everyone else. But that wasn’t what she meant. In my father’s death, I learned the truth. Dad, likely mom too, knew the whole time. In December 1976, my parents got a call from the adoption agency with the news of an available baby girl with one caveat. “You need to come see her,” offered the distant voice on the line. Because I was a biracial “special-needs” infant, the agency wanted to make sure that these adoptive parents, desperate to have a baby, would still be accepting of that baby if she wasn’t white.

“Does she have three eyes?” my comical father asked. The voice on the other end assured him two eyes, and that was all he needed to hear. My aunt’s revelation of that moment was also a revelation that my parents knew I was a biracial child.

After decades of inquiring, “Why do I look different?” “Do you think I am Black?” “Why did people call me the N word?” Now I was asking why did my parents hide the truth? Did my parents want to protect me from racism in a world where a non-white woman passing as white is better than a biracial woman knowing who she is? Was I in my beautiful biracial truth not enough?

Did my parents want to protect me from racism in a world where a non-white woman passing as white is better than a biracial woman knowing who she is? Was I in my beautiful biracial truth not enough?

Bethany Fraser

The adoption constellation is made up of many relationships that can be beautiful, complicated, and fragile. The more I share the more I know that having the courage to hold truthful conversations, no matter how uncomfortable, sets the stage for so much more. Confidence, communication, and connection all contribute to successful relationships. The next time you have a secret or a story, think of who you’re protecting by not sharing the story. Are you hiding? There’s healing waiting for you to be brave and honest. The most important healing comes to you and there you see your own beautiful mosaic.

The adoption constellation is made up of many relationships that can be beautiful, complicated, and fragile. The more I share the more I know that having the courage to hold truthful conversations, no matter how uncomfortable, sets the stage for so much more.

Tweet